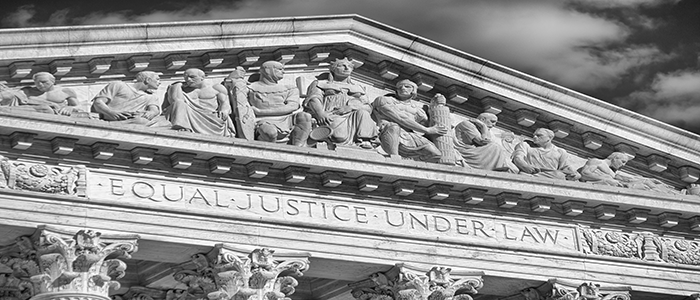

People should have access to the laws under which they are governed. That’s not just a high-minded ideal, it is actually the law under a very old decision of the US Supreme Court, Wheaton vs Peters (1834) — as it turns out, the first Supreme Court decision on copyright law.

“It may be proper to remark that the Court is unanimously of opinion that no reporter has or can have any copyright in the written opinions delivered by this Court, and that the judges thereof cannot confer on any reporter any such right.” (Wheaton v. Peters, 33 U.S. at 668.)

Sounds simple, right? Yet there’s a lingering issue concerning access to the laws of the various states, one of which has just reached (as of June 24th) the point of having its dispute slated for hearing by the US Supreme Court.

Public Resource.org and its issue with the State of Georgia

Carl Malamud, the founder and guiding spirit of PublicResource.org and “the Internet’s own Instigator” (according to WIRED) is engaged in a long-running battle with the State of Georgia over his publication of Georgia’s annotated laws. Although some states have long made their annotated laws available in printed form through publishers who, in their turn, charge users to receive copies of these works, asserting a form of copyright in them (as opposed to any copyright in the plain text of the laws themselves), the ultimate legitimacy of this practice has been called into question, and it (the issue) is really hitting the fan in Georgia, where the federal Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit has held that Georgia has no right to prevent Mr. Malamud, or, by implication, any member of the public, from accessing its annotated laws —and republishing them.[1]

The larger issue this squabble uncovers has been addressed in an advocacy article by Georgia residents Prof. Leslie Street and Librarian David Hansen in an article to appear in the Journal of Intellectual Property Law, entitled, “Who Owns the Law? Why We Must Restore Public Ownership of Legal Publishing.” Suffice it to say, regardless of which way SCOTUS decides this particular case, the issue is almost certainly not going away.

Building Codes and State Law

As in the old expression, “same church, different pew,” our friends over at TechCrunch recently reported on a case about access to and republication of building codes, which are also instances of state (or local) regulations, and the question is again about who has the right to publish or to restrict others from publishing them.

The International Code Council (ICC) is a not-for-profit company, set up in 1994 to help develop and publish the codes of building regulations across the 50 states. This is a useful activity, and the industry sponsors of the ICC see good reason for continuing to fund its operations. However, reliable building codes are not cost-free to maintain (especially as best building practices and available products change) and do provide a public good – buildings that stay up once erected, are safe to occupy, and so forth. UpCodes, a more recent entrant to the field (2015), is a SF-based startup with the aim to improve and disrupt the status quo in building codes – in short, their stated aim is to free the law.

One appeals court decision, Veeck v. Southern Building Code Congress Int’l, 293 F.3d 791 (5th Cir. 2002), appears to support at least part of the UpCodes/PublicResource view. Basically, the holding in Veeck answered the question “…may a code-writing organization prevent a website operator from posting the text of a model code where the code is identified simply as the building code of a city that enacted the model code as law? Our short answer is that as law, the model codes enter the public domain and are not subject to the copyright holder’s exclusive prerogatives. As model codes, however, the organization’s works retain their protected status.” (Emphasis added.)

In its amicus (‘friend of the court’) brief in the Georgia case, legal publisher Matthew Bender (a division of LexisNexis) makes an argument against the free distribution of the annotations of the Georgia Code, and for the commercial publishing arrangements which continue to be the status quo outside of the 11th circuit. The key distinction Bender draws is between the text of the law — “government edicts”— and the annotations which publishers like itself produce (as ancillary, original works, subject to their own copyright protection). These annotations are footnotes, endnotes or little essays about each provision of the statute, presented immediately adjacent to the text and including explanations of terms, references to cases and other materials, and other helpful information. As Bender’s brief puts it:

“The Eleventh Circuit’s decision needlessly destroys a thriving market for the creation of State-owned annotations by private publishers, which benefits the public’s understanding of the law and does not impose greater taxpayer funding obligations by the States. The necessary consequences of the Eleventh Circuit’s unprecedented decision will either lead to the States no longer offering statutory annotations or spending substantial taxpayer dollars to fund such annotations’ creation. The Eleventh Circuit’s decision will thus benefit no one, while undermining the core purpose of copyright law and the public’s understanding of the law. These annotations provide great benefit to the public’s understanding of law. The creation of these annotations is an expensive, labor-intensive process, requiring a trained attorney to read judicial and agency decisions and make sensitive judgments about the annotations’ contents. Annotations provide users with a wealth of information about how the statutes came to be, how they have been interpreted by courts and agencies, and the like. These works have long been properly protected by copyright law, providing an incentive for their creation. But if annotations can now be copied and posted on the Internet for free by groups such as [Public.Resource.org] as unprotected “government edicts,” this will destroy LexisNexis’ ability to recoup the substantial costs of the annotations’ creation. This will inevitably lead to the discontinuance of publicly-valuable contractual arrangements for the creation of such annotations, as soon as current contracts expire, causing needless harm to States and the public.”

For my own part, I’m not yet sure who I believe might have the better argument in these disputes —and I am very much looking forward to SCOTUS reviewing the Public.Resource case in its next session. To my mind, the principle articulated in Wheaton v. Peters—that public access to the laws (including agency regulations) is fundamental in a democracy—certainly needs to be upheld. And yet, there’s also clearly an important public benefit to publishing those regulations —as well as state-recognized codes and standards—in a timely and coherent manner, along with annotations and other publishing value-adds which help render them more understandable to interested readers — yes, including lawyers but also the general public. Which is to say, the business of publishing quality materials, which still (even post-Internet revolution) entails dollar costs, and those costs must be covered somehow.