This article originally appeared in The Scholarly Kitchen

As scholarly communication rapidly adapts to seismic shifts in open science, technology, and culture, a renewed focus has emerged on metadata and persistent identifiers (PIDs) — about people, places, and objects — as an essential component of a vibrant industry. At the US policy level alone, leveraging metadata to accelerate industry transformation is a common theme across the Nelson Memo and recent Requests for Information from the NIH and the Department of Transportation.

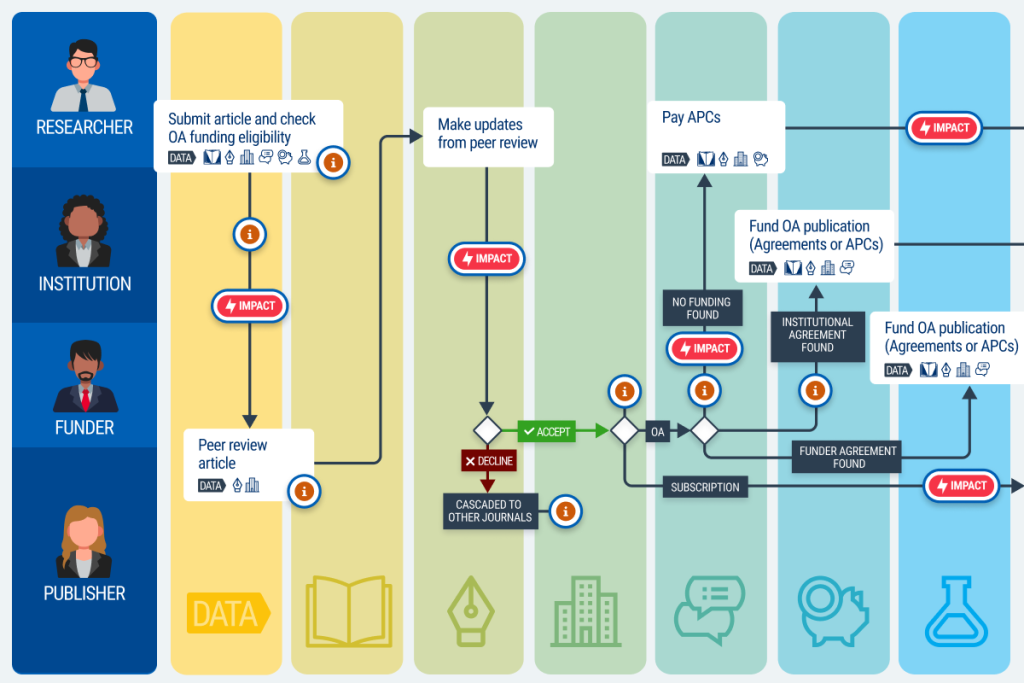

Scholarly research is complex and interconnected; change in one area can spark improvement or deterioration throughout the ecosystem. By way of example, consider the role of PIDs in open access (OA) funding entitlements. OA management platforms rely on metadata elements, particularly organizational PIDs passed from upstream submission and peer review systems, to automate the process of matching manuscripts with potential funding sources. This typically happens at article acceptance, and increasingly at submission, eliminating manual administration for authors as well as supporting publishers, institutions, consortia, and funders in achieving OA at scale.

In order to perform a health check on organizational IDs, in 2021, we reviewed cross-publisher records of institutional affiliation and/or funder data in our OA workflow tool, RightsLink for Scientific Communications. We discovered that 82% of accepted manuscripts included such data, which was an improvement over prior years. However, these statistics masked an ugly truth; namely that in many cases those manuscripts used institutional email domains as a proxy for funding or discount eligibility instead of a PID. And within the 18% that carried no PID, missed funding opportunities created unnecessary work (and payments) for authors, institutions, and publishers to reconcile retroactively.

Even if CCC — either alone, or with its partners and publishers — were able to close these metadata gaps at acceptance of manuscripts, this is late in the process and advantages of PIDs earlier in the research lifecycle would be lost. Solving for metadata gaps would be more effective in upstream systems of record so the tail doesn’t wag the dog. This is precisely why we’ve encouraged the NIH to consider the grant application process as an early opportunity to mandate PIDs and cascade to other systems underpinning the research lifecycle, for example, Current Research Information Systems (CRISs).

But where to start? Let’s face it, PIDs are a wonky topic and we need to communicate to people who are not naturally interested in the intricacies of, e.g., ISNI and Ringgold. But these people will care if they know that lack of PIDs can lead to lack of funding. In order to break this down, we recently talked with dozens of stakeholders and mapped a range of metadata challenges through an OA lens. We built on an existing body of work to visualize the ripple effect of a fragmented metadata supply chain. The result is an interactive report of the research lifecycle designed to offer everyone a deeper understanding of the state of scholarly metadata in 2023. Though the issues are numerous, they are not insurmountable, and much infrastructure exists to support change.

About the State of Scholarly Metadata: 2023

Working with Media Growth Strategies, we interviewed representatives from institutions, publishers, funders, researchers, service providers, PID providers, and industry associations to capture a broad view of the current state of metadata and PIDs across the ecosystem. We asked questions such as:

- Who should create and maintain metadata? Where should it originate?

- What resources do you invest to create, curate, or maintain various types of metadata?

- What are your biggest challenges when it comes to metadata management and/or use of PIDs?

- What are the most critical metadata elements?

- What’s at stake if these elements don’t persist through scholarly communications?

- Who should own metadata quality and control?

Here is what they said about the costly implications of metadata breakages and complexities across the research lifecycle:

- Researchers: There was overwhelming consensus among stakeholders that researchers shoulder a significant administrative burden to assert or re-assert data (e.g., institution affiliation, funder ID), ultimately disrupting and delaying scientific discovery.

- Institutions: Because of metadata inconsistencies throughout the research lifecycle, institutions deploy labor-intensive workarounds to manually reconcile funding eligibility and APC billing, as well as normalize unstructured data across disparate systems for comprehensive analysis.

- Funders: Missing metadata (e.g., registered grant DOIs, institution affiliation) makes it difficult and costly to link funding to research outputs, presenting potential barriers to open access uptake, problematic impact tracking, and incomplete analysis to inform future investments.

- Publishers: Metadata breakages interfere with business transformation initiatives, contributing to high operational and opportunity costs and complicating fulfillment of open access agreement terms and analysis of deal performance to inform future decisions.

Many stakeholders we interviewed recognize that new metadata strategies, inclusive policies, and a robust framework of interoperable systems are essential for modernizing this element of scholarly communications. It’s also clear that an ecosystem-wide commitment to improving data quality across all groups will facilitate the transition to open while helping to preserve research integrity, expand discoverability, and improve impact measurement. If the industry works collectively to shrink these gaps by reexamining metadata policy and practice, stakeholders will undoubtedly feel less pain. Or, we can continue the current system of entropy, friction, and frustration. Together, we can decide our path.